Last week I published a short story for Christmas: The Volcano, or the Rival Harlequins: A Dan Foster Mystery. It’s December 1799 and the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden is presenting its Christmas pantomime. Dan Foster, Principal Officer of Bow Street, is assigned to the theatre to help keep order. What begins as a tedious assignment turns into a murder investigation when a stage trick goes horribly wrong. But how can Dan identify a murderer when all the suspects are experts in disguise and concealment?

There really was a play called The Volcano, or the Rival Harlequins and it really was performed at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden in December 1799. It was written by Thomas Dibdin, and it starred one of the eighteenth century’s best known clowns, Carlo Delpini. In true eighteenth-century style I have shamelessly borrowed the title for my Christmas story. Thomas Dibdin appears in the story as Tom Merchant, the name he used when he started his career in the theatre.

One of the major inspirations for the story was a production of R B Sheridan’s 1779 play The Critic, which I saw at the Chichester Festival Theatre in 2010. It was on a double bill with Tom Stoppard’s The Real Inspector Hound. They were performed by the same cast, which included Richard McCabe and Una Stubbs. Both plays were wonderful, but The Critic was one of the funniest things I have ever seen. To this day I can still see Joe Dixon’s Don Whiskerandos strutting hilariously about the stage. As for the scene that inspired the story, it was a piece of stage machinery that, apart from filling me with admiration for the steadiness of McCabe’s nerves, got me thinking: what would happen if it had gone wrong?

The other inspiration was, of course, the Christmas pantomime. It was already popular in the eighteenth century, though in a very different form from what we know as pantomime today.

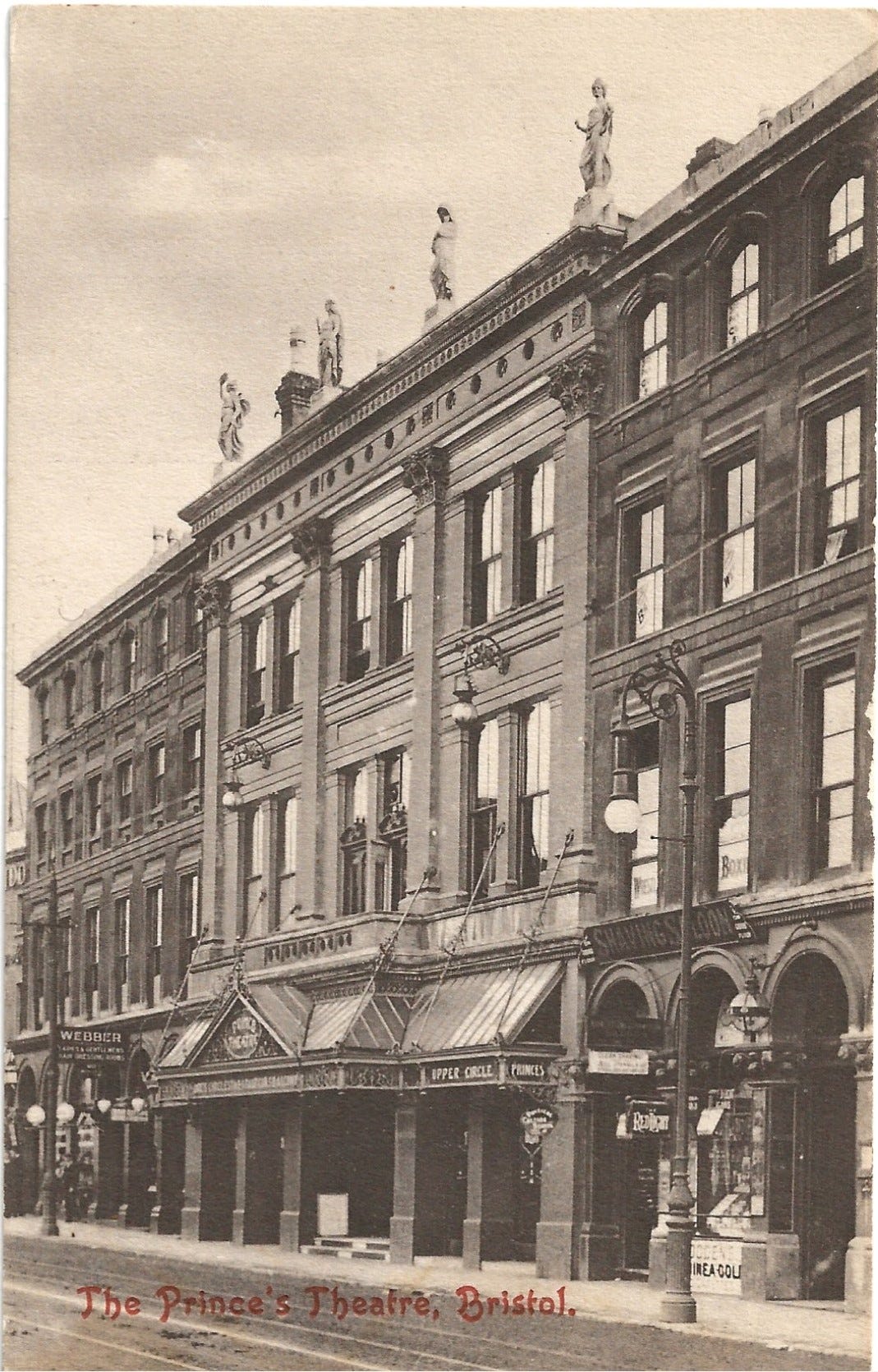

The Princes’s Theatre, Bristol, known as “the home of pantomime”, starting with Aladdin in 1867, and continuing until 1940, with 72 productions to its name.

The pantomime has its roots in the Italian tradition of commedia dell’arte, which dates back to the sixteenth century. The commedia, performed on the streets and in fairs, was spread across Europe by travelling players. They wore masks, improvised their parts, and played stock characters. These included Harlequin and Columbine, who were originally servants and often romantically linked; Pantaloon, a wealthy merchant; and Il Dottore, a pompous old man. In France, Pierrot was a popular addition. The plots usually involved two couples with guardians or parents who attempt to separate them; greedy and irrepressible servants who thwart the old men; and music, dance, slapstick, acrobatics and magic.

In the 1720s John Rich, a British dancer, acrobat and mime artist, introduced the harlequinade to his theatre in Lincoln’s Inn Fields. His new-style spectacles thrilled audiences with incredible set transformations and effects such as fire-breathing dragons and working mills, animal characters played by humans (skin characters), music, ballet and cross dressing. However, there was no spoken dialogue, and these early pantomimes were divided into two parts, a serious section followed by the comical harlequinade.

Columbine and Pantaloon

The Licensing Act of 1737 restricted the performance of dramatic plays to the two Theatres Royal at Drury Lane and Covent Garden. They were thus the only theatres allowed to produce spoken drama. All the other theatres had to rely on music, mime, song and dance, all of which were of course already integral components of the harlequinade.

Many critics looked down on the harlequinade and deplored its impact on “serious” theatre. John Garrick, manager of Drury Lane Theatre, refused to have pantomimes performed in his theatre. Eventually, though, he realised he could not afford to be so sniffy, and on Boxing Day 1750 the first Drury Lane harlequinade was reluctantly presented. Formerly, pantomimes would be performed at any time of the year, and were particularly popular at Easter. Garrick confined his pantomimes to Christmas, and eventually the pantomime came to be associated exclusively with Christmas festivities.

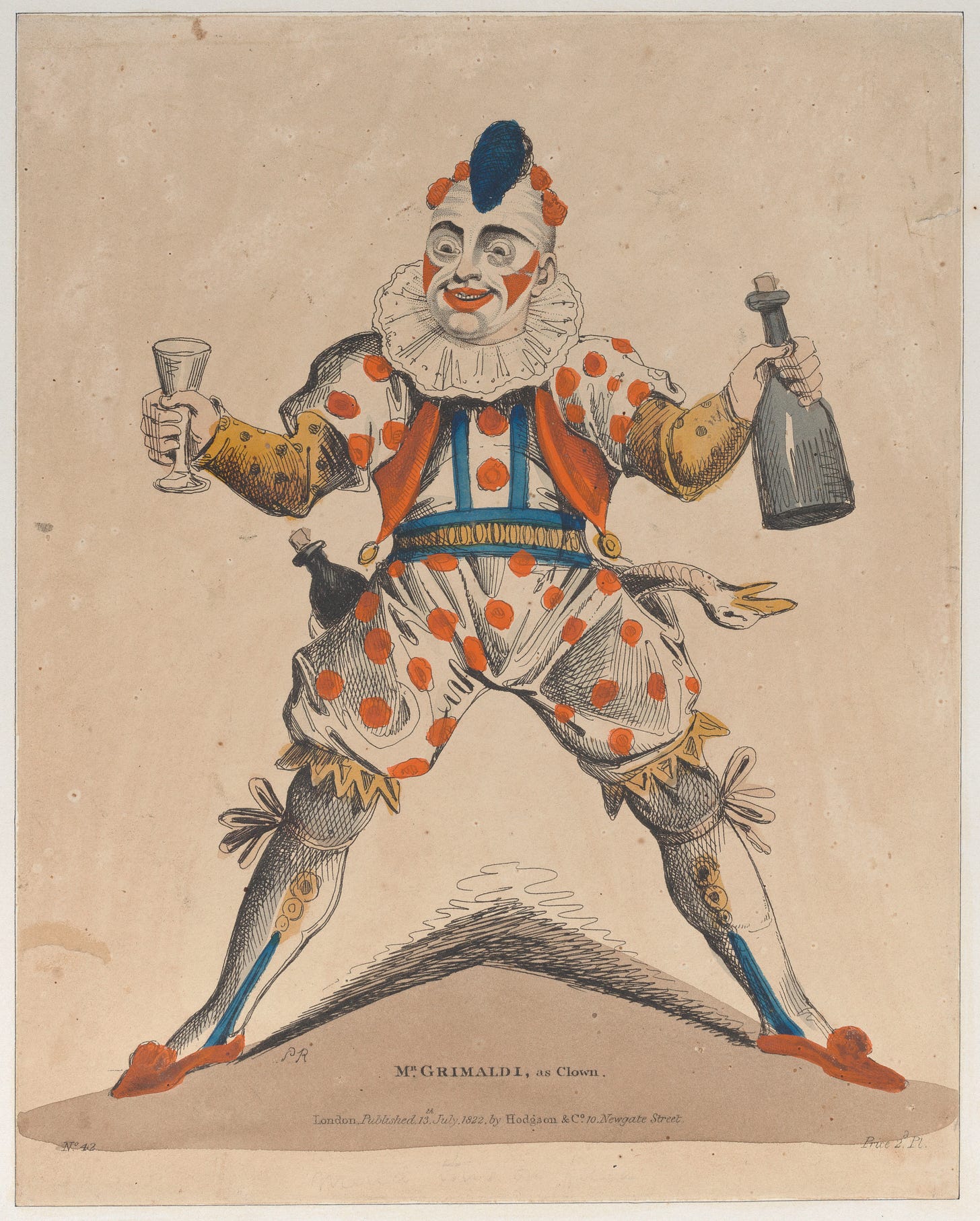

In time the serious part of the pantomime gave way to the harlequinade, which took over the entire production. The Pierrot developed into the more familiar figure of the clown, and Harlequin disappeared. It was Joseph Grimaldi, one of the eighteenth century’s most famous clowns, who developed the anarchic character we know today. Grimaldi painted his face, wore colourful costumes, sang comic songs, and played numerous tricks and gags. Some of these are still used in modern performances, such as the string of sausages that comes to life or the butter slide. He also used catch phrases (“Here we are again!”).

The Theatre Act of 1843 lifted the restrictions on the use of spoken dialogue so that all theatres were now free to produce plays. This facilitated further developments in the pantomime. In came patter, quick-fire gags, double entendres and audience participation (“It’s behind you!”).

The nineteenth century saw the development of the pantomime dame, who eventually ousted the clown. In addition, many stars of the music hall performed in pantomime, starting the tradition of the star appearance in the Christmas pantomime. One of the most famous pantomime dames was the music hall star Dan Leno, whose roles included Widow Twankey in Aladdin. The tradition of a woman playing the Principal Boy also became popular.

The Theatre Royal, Drury Lane’s production of Sindbad in 1907

The original pantomimes were not intended for children, but over time they became much more family friendly. Many of the cruder aspects were removed or toned down, such as the depiction of cruel and violent practical jokes. Charles Dickens referred to one pantomime as “not by any means a savage pantomime, in the way of burning or boiling people, or throwing them out of the window, or cutting them up”. It makes you wonder what a savage pantomime looked like! Today the pantomime is an entertainment which appeals to all the family, and is as much a part of Christmas as cards and crackers.

The modern pantomime is very different from the productions that delighted audiences three hundred years ago. Yet with its blend of tradition and innovation I don’t think it would be completely unrecognisable to our ancestors. In fact, I like to imagine that if Joseph Grimaldi shot onto the stage through one of the traps, shouted “Here we are again!”, and pulled a string of sausages out of his pocket, he wouldn’t look at all out of place.

“Here we are again!” Joseph Grimaldi

Picture Credits

The Prince’s Theatre, Bristol - Postcard, Author’s Collection

Columbine and Pantaloon, German, Meissen, The Jack and Belle Linsky Collection, 1982 Met Museum of Art, Public Domain

Actors in the pantomime Sindbad at Drury Lane, 1907, Wellcome Collection, Public Domain.

Mr Grimaldi as “Joey” the Clown, 1822, Possibly Piercy Roberts, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund 1917, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public Domain