The Volcano, or the Rival Harlequins

A Serio-Comic Pantomime

Performed at the Theatre-Royal, Covent Garden, December 1799

With entire new Music, Scenery, Machinery, Dresses and Decorations

Of all the places he might have been on duty, this was the one Dan Foster, Principal Officer of Bow Street Magistrates’ Court, liked least. Walking alone and unarmed into a flash house to nab a burglar, or kicking down a door in a St Giles rookery to pluck a robber from the midst of his gang, would have been preferable. Instead, he was at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, where his duty was to keep swarms of pickpockets away from theatre goers so festooned with watches and snuff boxes, jewellery and silks, they might as well have carried placards saying “help yourself”. But it was Christmas: the shops were busy, the streets were busy, the taverns and dining clubs were busy, and the officers and patrolmen of Bow Street were busy, trying to keep order among the holiday crowds, or at least prevent by their presence the worst kinds of crimes.

Which in the case of the Theatre Royal, Dan had not succeeded in doing. After making the rounds of the staircases, landings and passages around the private boxes, he had gone downstairs to see how the two patrolmen stationed in the pit were coping. They and a third man on the door were the only force he had to police a theatre packed to the rafters for the theatrical event of the season: the Christmas pantomime, The Volcano, or the Rival Harlequins.

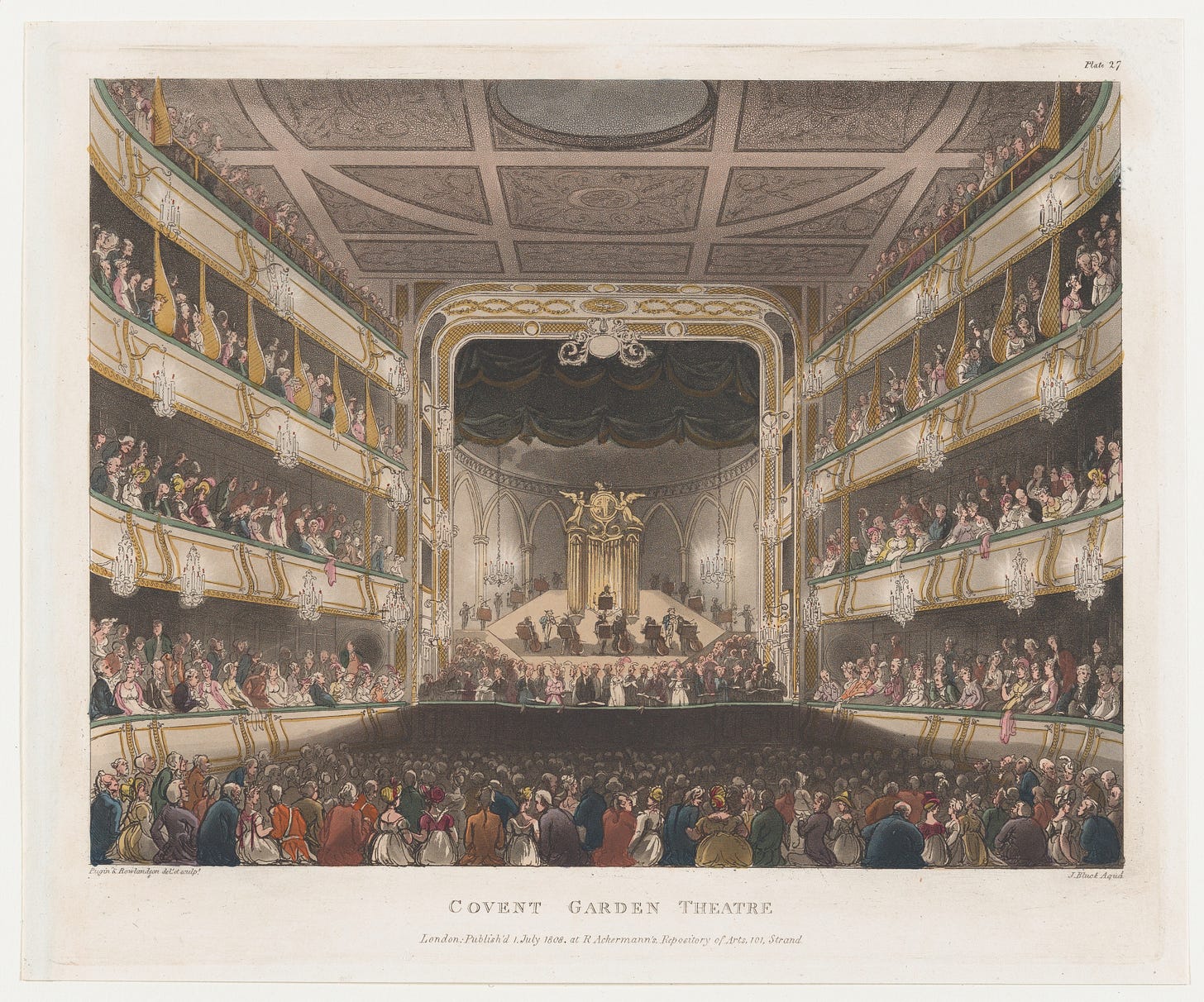

The Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, London

Dan had prowled at the edge of the auditorium, scanning the rows of upturned faces as he passed. Occasionally, he had glanced at the stage, but mostly avoided it. With their strutting, shouting, posing, prancing, constantly breaking into song, and fol de lal lalling their way through their tedious business, actors irritated him. He had steadfastly kept his eye on the shadier types skulking in the audience on the lookout for unguarded purses. Their heedless owners’ attention was fixed on sword fights and dances; flying spirits and demons; Irish ballads and lovers’ duets; a volcano which turned into a tea garden; a cottage that became a temple; a forest that became a lady’s boudoir; and many other astonishing transformations.

But even Dan had been transfixed by the final spectacle before the curtain came down. The scene was a corn field with a working windmill centre stage. With the rest of the audience he had gazed at the crashing scenery, the whiplashing ropes, and the clouds of dust as the building tumbled onto the head of Harlequin Trueheart.

The other actors – Mercantilio, Columbine, the Clown, and Harlequin Foulheart – had been frozen in their various situations on the boards. It was Foulheart who had been first to recover his wits and rush to the fallen actor to try to save him. It was too late: the man was already dead.

Now the stagehands had dragged the debris aside, lifted out the body, and carried it away, covered in a sheet that was quickly soaked crimson. Dan, crouching down to examine the ground, snapped his fingers at the trio of patrolmen who stood nearby waiting for instructions.

“Bring over that light.”

One of the men came forward and tilted a lamp to illumine the bloodstained area beside the tangle of wood, metal and canvas.

The stage manager followed him, his hands pressed to his white face. “It’s not possible! We’ve worked on this machinery all summer. The actors rehearsed it a score of times. It’s been checked and checked again. It can’t go wrong.”

Dan ran his hands over the bright yellow cross that had been painted onto the boards. “How is it supposed to work?”

“The windmill transforms to a ship so the lovers Harlequin Trueheart and Columbine can escape from the wicked Harlequin Foulheart and her father, Mercantilio. The Clown taps it with his magic stick, the walls fall down, the mast goes up and when the mechanism has finished running, Trueheart appears at the helm with the sails billowing behind. The X marks the spot where he should stand. He’d have been perfectly safe there; the scenery would have fallen around him. He must have been standing in the wrong place.”

“I think he did stand where he expected to be safe.” Dan pointed at the floor. “Do you see that?”

The stage manager leaned forward and squinted at the yellow lines. “I don’t—” Understanding dawned. “There’s another cross.”

“That’s right.” Dan traced the faint outline of the shadow cross. “The original mark has been painted over and this one has been substituted for it. This wasn’t an accident. You didn’t notice it had been repainted when you checked the machinery?”

“No. It’s exactly like the original, the exact same colour. I mixed the paint myself.”

“Has any gone missing?”

“Why, yes! A pot of the yellow went missing from the store yesterday. I noticed it after rehearsals. A brand-new tin, unopened. I thought someone had pilfered it and taken it home.”

Dan stood up. For a moment he gazed out at the rows of empty seats, the tiers of vacant boxes, the floor littered with shawls, hats and shoes left by the fleeing audience. “Where are the principal actors?”

“In the green room. I’ll show you.”

Dan jerked his head at the patrolman with the lamp. “You’re with me. You two, search the dressing rooms.”

***

Dan heard the actors before he reached the green room, the babble of their voices accompanied by a woman’s sobs.

“You said you’d kill him!”

“And you swore you’d swing for him! And you threatened him to his face.”

“Gentlemen – gentlemen—”

“Don’t you interfere, Mistress Dresswell. If it comes to it, you said poison would be the best way.”

“And I saw you aim a pistol at his back.”

“It was a stage pistol, fires nothing but a flash!”

Dan nodded at the patrolman to open the door. Silence fell and six startled faces turned towards him.

The actors were grouped in a semicircle of chairs to the side of the hearth, where a meagre fire burned. There was a table with a model of one of the stage sets on it, surrounded by used plates and empty glasses. Notices from the management had been pinned on the wall over the mantlepiece, threatening fines for various transgressions, such as lateness or extemporising. Nothing about murdering one another though. The room was lit by candles placed here and there, but the corners were dim.

On the left sat Harlequin Foulheart, a wickedly handsome young man in a costume patterned with red, yellow, blue and green diamonds, the gaiety of which did not match his glum expression. He was holding a black eye mask, which he twisted between nervous fingers.

Next to him sat Mercantilio, an older man, though not so old as the thick dark lines drawn on his face suggested. He wore the velvet robe, gold chains and trinkets associated with the wealthy and avaricious merchant father of the heroine, Columbine.

His rebellious stage daughter sat on a stool at the end of the row leaning on the knees of a homely matron whose bodice glinted with rows of pins, and from whose belt hung scissors, a packet of needles, coils of variously coloured threads, and other tools of the theatrical dresser’s trade. Mrs Dresswell had her protective arm around Columbine, whose bland prettiness was marred by red eyes and a blotched complexion. In spite of these disadvantages, the girl fluttered her wet eyelashes, pouted her cherry lips, and shook her golden curls at the tall, dark Bow Street Officer.

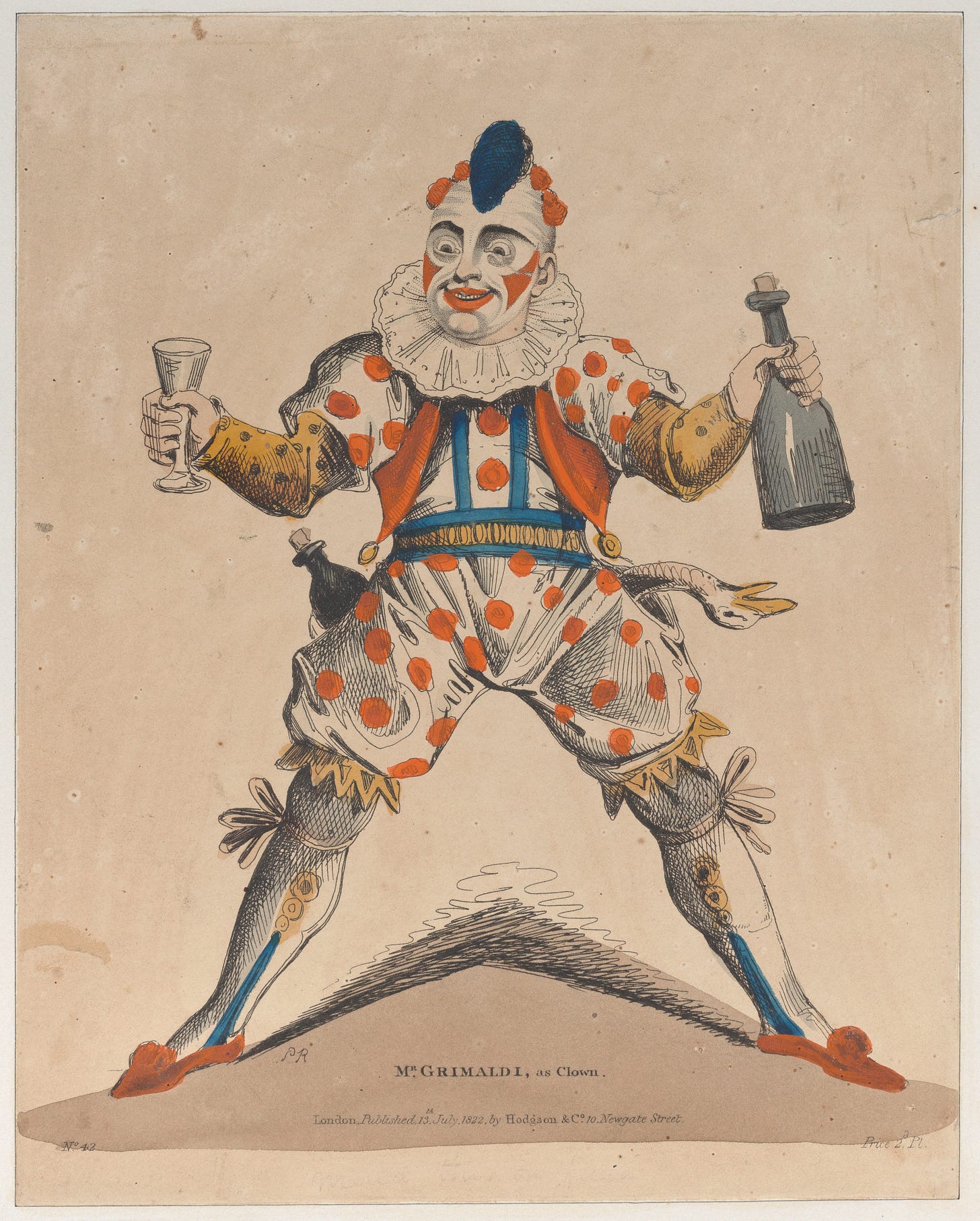

Dan only glanced at her. He gazed at the man who sat in the centre of the row. He had a brilliantly white face; his cheeks and chin were daubed with triangles of violent red; and he had painted eyebrows that arched as high as his hairline. He wore a blue wig brushed up into tufts, a stiff white ruff around his neck, ribboned pumps, a striped doublet that was too small for him, and spotted breeches that were too big. Why anyone found the Clown funny was beyond Dan, but apparently they did, for his appearance had been greeted with roars of laughter whenever he tumbled acrobatically onto the stage.

Harlequin and Columbine

The company was completed by a tall man standing behind the actors, half-hidden in the shadows. He was not in theatrical costume, and next to the actors’ finery his clothes seemed almost Quakerish. From what Dan could see of him, he had an intelligent, thoughtful face with something of the Roman patrician about his long nose and well-shaped mouth.

“From what I just overheard,” Dan said, after the patrolman had introduced him to the awed group, “it seems you all had a reason to wish the victim dead. So let’s start with those, shall we? Who would like to go first?”

Apparently no one would.

“I could take the lot of you to Newgate and see if you’re more talkative there.”

Mercantilio pointed at Harlequin Foulheart. “Why don’t you tell him how Trueheart made you look like a bumbling amateur? He was always interrupting your speeches, standing in front of you, and putting you off your stride with his improvisations.”

“A bumbling amateur?” cried Foulheart. “You were cast to play Trueheart yourself until he hinted to the management that your drinking made you unreliable. Which is true, by the way. You’re always missing rehearsals. And what about you?” He waved his mask in the direction of the Clown. “How many times have you told us the tale of his ingratitude? How you helped him in the early part of his career, got him parts, shared your lodgings with him, loaned him money which he never paid back?”

“That is what true brethren of the sock and buskin do for one another,” the Clown replied in a grand manner. “It is our tradition, though boys like you would know nothing of that. Besides, isn’t it obvious who has the strongest motive to kill Trueheart? Mrs Dresswell and her daughter, our fair and wronged Columbine. What stronger motive than to protect a lady’s honour?”

“Which was surely past protecting long ago,” Mercantilio sneered.

“You will take that back, sir!” cried Foulheart, springing to his feet.

“I will not, sir,” returned Mercantilio, leaping up to face him.

The two men glared at one another. The Clown clutched at Mercantilio’s robes and tried to pull him back into his seat, Mrs Dresswell extracted a pin from her bosom, perhaps with the intention of using it as a weapon, and Columbine wailed more loudly than ever.

“Don’t you think—” began the Roman in the shadows.

His mild voice was lost in a chorus of threats and insults which looked likely to end in fisticuffs if the sudden opening of the door and the entrance of a patrolman carrying a pot of paint had not distracted them. Mercantilio and Foulheart sat down.

“I found this in the Clown’s dressing room, sir,” the patrolman said, handing it to Dan.

“What? How? Why?” spluttered the Clown. “I have never seen that before in my life!”

“Come to think of it,” said Mercantilio slowly, “I saw you loitering near the scene painter’s store after yesterday’s rehearsal. There was no mistaking you. You were still in costume.”

The thunderstruck company stared at the Clown and shuffled their chairs away from him.

“Wouldn’t it be better—” attempted the mild voice from the gloom.

“I never went anywhere near the store!” the Clown cried. “I have no idea how the paint got into my room. Why it did is plain enough. It is a wicked attempt to lay the crime at my door.”

“And those are the desperate words of a guilty man,” Mercantilio retorted.

“One wicked enough to blame an innocent woman for his own doings!” Mrs Dresswell added, clutching the wronged Columbine closer.

“Innocent!” muttered Mercantilio.

“You never made any secret of how much you hated him,” Foulheart reminded the Clown.

Joseph Grimaldi (1778–1837) the popular eighteenth-century clown

Impossible though it seemed, the Clown’s red cheeks bloomed redder than ever. He seemed in danger of exploding when the door opened again and the third patrolman came in carrying a bundle over his arm. Dan listened to his whispered explanation, then shook out the fabric and held it up to reveal a clown’s costume, the sleeve stained with yellow paint.

“This was found stuffed at the bottom of the trunk in your room,” Dan said.

The actors turned astonished eyes on Harlequin Foulheart.

“I never put it there!” Foulheart protested.

The Clown gasped. “That’s the costume that was stolen from Mrs Dresswell’s room last week. I gave it to her because a button had fallen off.”

“Why, so it is!” cried the lady. “It was taken before I had a chance to mend it. You can see the threads hanging.”

At the word “hanging” Foulheart groaned.

The Clown pointed an accusing finger at him. “You had it all this time!”

“I did not! I never laid hands on your costume.”

“Ah, but I see how it is,” the Clown said, shaking his head gravely. “You stole my costume, you wore it as a disguise, you murdered Trueheart, and then you hid the paint in my dressing room to incriminate me.”

“I did no such thing!” insisted Foulheart, who by now had shredded the mask into several pieces.

Mrs Dresswell screeched. “I saw you go into his room! I remember it now. It was just before the end of the first scene.” She turned to Dan and explained, “I had my door open. I always open it at that time ready for the dancing demons. They’re terrible for splitting their seams, those demons. My room is opposite the Clown’s and I saw him go inside.”

“You saw Harlequin Foulheart go into the Clown’s room?” asked Dan. “Was he carrying anything?”

“Not that I could see, but by then the demons were queuing up.” She rounded on Foulheart. “And don’t you dare deny it, and call me liar.”

“I don’t deny it,” Foulheart said. He looked at the Clown. “You said I could go in to borrow some of your make-up.”

There was a chorus of shocked gasps. It was followed by a dreadful silence, then one and all edged their seats away from Foulheart and closer to the Clown. In every face suspicion of guilt had turned to certainty. None of them could bring themselves to look at the man who now sat condemned before them.

“I don’t understand,” stammered Foulheart, gazing at his erstwhile colleagues in bewilderment.

Nor did Dan. “What just happened?” he demanded.

They all looked at the Clown, but he was too overwrought to speak.

“It’s the make-up,” Mrs Dresswell said at last. “A clown never shares his cosmetics with any other actor. It’s his closely guarded secret.”

“He would never have said such a thing,” Mercantilio confirmed. “Foulheart is lying.” He looked sorrowfully at the younger man. “It was you who painted the cross. Allowing time for paint to dry, it must have taken all night to cover over the old cross and paint in the new. That’s why you were here so early this morning. It being such an unusual circumstance, I made a jest of it, do you remember? I asked if you’d fallen out of bed. But you’d been here all night, hadn’t you?”

“No. I came in early because I didn’t want to have my pay docked for lateness again.”

Mercantilio folded his arms. “Hah!”

The Clown raised his eyes to heaven. “Oh, cruel, cruel, when a fellow thespian assumes the evil nature of the thing he affected – a foul heart!”

“Oh Jack, how could you!” wailed Columbine.

The Clown covered his eyes with his hand and said tremulously, “It’s time to make an arrest, Officer. Spare us the sight of this horrid villain.”

“You’re right,” Dan said. “It is time to make an arrest.”

He reached into his pocket and drew out his handcuffs. Foulheart rose slowly to his feet. His face was pale, but he squared his shoulders and held his head high.

“As God is my witness, I am innocent,” he said.

The patrolmen edged towards him. Dan snapped the cuffs open. The company huddled together, staring at Harlequin Foulheart in horror.

Dan spun round and confronted the Clown.

“I’m arresting you – what is your name? I can’t keep calling you Clown—”

“Albert Parsons, sir,” supplied one of the patrolmen.

“I’m arresting you, Albert Parsons, for the murder of—”

“Charles Sloper, sir.”

Parsons the Clown sprang to his feet, his eyes wild, spittle flying from his mouth. He drew out a knife from the depths of his baggy breeches. “Don’t come near me! I’ll use it!”

None of the actors needed warning twice. They bolted out of their seats, knocking them over in their flight. The patrolmen glanced at Dan, who nodded at them to step back.

“Let him go.” Dan grinned. “We’ll circulate a description: clown.”

The Clown shot a look of hatred at him and ran for the door, lowering the blade as he did so. He did not get far. Dan’s right fist flew out and hit him square on the jaw. The knife clattered to the ground, his eyes rolled up in his head and he crumpled, unconscious, to the ground.

The patrolmen dragged Parsons off to Bow Street and the actors filed silently away, avoiding one another’s eyes. Left alone in the green room, Dan took a handkerchief out of his pocket to wipe his crimson knuckles.

A voice came out of the shadows. “How did you know?”

Dan looked up. The man who had stood silently by was still there. He picked his way over the scattered chairs and emerged into the light.

“Who are you?”

“Tom Merchant.” He bowed. “I am the author of The Volcano, or the Rival Harlequins.”

“Are you?” said Dan, unimpressed. “And what is it you want to know?”

“How you knew the Clown was the murderer and not Jack – Harlequin Foulheart.” Tom smiled. “It’s usual, you know, to have a scene explaining everything at the end.”

Dan laughed and shook his head, but the look of interest on Tom’s face was so keen he decided to indulge him. He lowered his handkerchief.

“It was the costume. I suppose it was only natural for an actor to think it would fool everyone. If someone was going to steal a pot of paint, why would he wear such easily recognisable clothes, unless he wanted a clown to be seen behaving suspiciously? But anyone can wear a clown outfit, and it so happened that one was stolen from Mrs Dresswell’s room last week, one that was easily identifiable by the missing button. When that costume turned up in Harlequin Foulheart’s dressing room, complete with paint stain on the sleeve, the obvious conclusion was that he took it and wore it in order to lay the blame for the murder on the Clown. In fact, it was the other way around.”

“The Clown stole his own costume and left it in Jack’s room?”

“Yes. At the same time, he made it look as if Foulheart left the pot of paint in his own room. He knew that Mrs Dresswell would have her door open at the end of the first scene, and that she would see Foulheart. And when he came up with a story no one would believe – that the Clown said he could borrow his stage make-up – what could be more obvious than that he had gone in to leave the paint on the dressing table? But it was clumsily done. No murderer would leave so incriminating a piece of evidence in plain view.

“And then there’s that paint on the clown costume. The stage manager told us the stolen pot hadn’t been opened, so the murderer couldn’t have got any paint on his clothes when he took it from the store. That being so, he must have worn the clown disguise when he was painting the new cross. That makes sense, doesn’t it?”

“Yes.”

“No. The theatre is empty at night. There was no one here to see him and so there was no need for a disguise. Why would anyone wear so cumbersome an outfit to paint in?”

“The Clown daubed the paint on the costume before he put it in Jack’s trunk.”

“That’s right. I’ll own it was a clever plan, and a bold one, to convince us of his innocence by making it look as if the blame was being falsely laid on him, when in truth it was the Clown who was incriminating Foulheart.”

“So the Clown was pretending to be Foulheart pretending to be the Clown! It’s perfect! I’m certain it has never been done before. Of course, I’ll have to change the characters, give them new motives, a different setting – a country mansion, I think. We can keep the young lovers, the tyrannical father, and the villainous suitor, perhaps add in a rich uncle, a chambermaid, an innkeeper and some yokels. What about a ghost? No, no ghost. We’ll have a chase across a windswept heath, a duel, highwaymen hiding out in the forest, and the punch when you arrest him at the end can be a regular set-to. Perhaps we can get a champion like Dan Mendoza to demonstrate the fistic art. There’s never been a Bow Street Runner represented on the stage! Jack has the same build as you, and with the boots – nice touch, by the way – the coat, and the hat, will do very well.”

“Wait a minute! Are you intending to turn this into one of your stage plays?”

“Of course! It will be the talk of the season.”

“It won’t, because you’re not going to write the play.” Dan raised his right hand, stretched out his fingers and slowly bunched his gory fist. “I wouldn’t like it.”

Tom turned pale and backed away. “Of course – no harm meant – wouldn’t dream – just my little jest – no intention of ever—”

He reached the door, opened it, and fled. Dan, listening to his footsteps racing along the corridor, smiled to himself, shook out his handkerchief, and slowly wiped the clown’s red face paint off his knuckles.

The End

Picture Credits

The Theatre Royal Covent Garden, 1808, Thomas Rowlandson, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, The Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1959 Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public Domain

Harlequin and Columbine with Birdcage, Ansbach Pottery and Porcelain Manufactory (German, 1758–1860), Gift of Irwin Untermyer, 1964, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public Domain

Mr Grimaldi as “Joey” the Clown, 1822, Possibly Piercy Roberts, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund 1917, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Public Domain